Adult Martial Arts: Considerations

What makes adult martial arts different from children/kids martial arts? Is it maturity, vocabulary, prior education, or even social standing? What considerations should an instructor embrace, when outlining a curriculum and teaching a group of students? Let’s explore some of these considerations, and compare some key differences to better understand how to properly tailor the proper message for the desired audience.

Maturity and Responsibility

I would sum up the difference between adults and children in a single word: responsibility for one’s actions. There is a certain amount of unspoken vicarious liability when teaching children how to effectively defend themselves, when self-defense may involve violence towards others - especially when we consider that these violent actions may injure other children. At this stage, the teacher (not the child) has primary responsibility.

However, once a person is considered an adult (18 years of age in most jurisdictions) they are held solely accountable for their own actions and will be judged according to the laws of the land. They are not only responsible for their actions, but they also cannot shed that responsibility as easily as a child. From a teaching perspective, it is also easier to accept the fact that an adult may injure another adult in a physical application of self-defense - it just sits better with us.

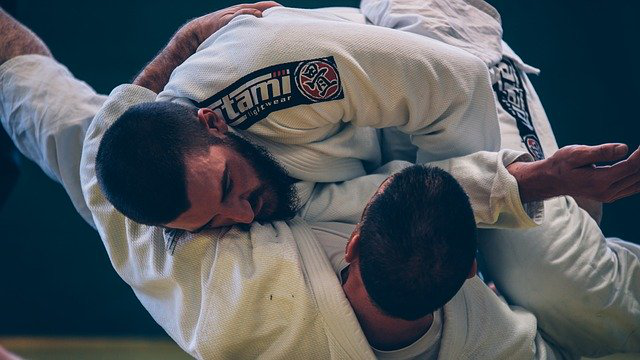

Caution is obviously required when teaching anybody - whether it be adults or children - but a greater degree of caution must be exercised when selecting and teaching children. This translates into an understanding that adults are generally given more freedom to explore and learn a greater variety of defensive and offensive techniques that have a greater potential to injure their attacker. There is also an expectation that an adult’s judgement and actions will be more appropriate to the situation, and if adults are overzealous in their application, the results generally fall upon them. This makes practical sense and is a socially responsible practice with regard to teaching martial arts.

Understanding these differences in personal responsibility is critical when formulating your teaching curriculum. As an example, we can see a measured choice in matching curriculum with responsibility, when we look back at Karate’s development in the early 20th century. Karate during this time can best be described as a form of self-defense “combatives” that focused primarily on nullifying physical confrontation, often in a violent fashion. A deeper study of the meaning behind the movements to the original Okinawan Katas reveals a surprising amount of crippling techniques that can mame or injure an opponent for life (or even worse). When Karate was introduced to the first middle school in Okinawa between 1900 and 1910, the old masters realized they could not teach these techniques to children - they simply were not proper for the age-range. So they had to alter the meanings (and sometimes, the techniques) to Karate, in order to reduce the level of violence, and make the curriculum more acceptable for children (while still providing a viable means of self-defense).

Mental and Physical Development

In turning the page, however, the level of maturity and responsibility is not the only focus of comparison. Another key factor to consider when comparing adults to children is the difference in mental/physical development. Developmentally, children between the ages of 6 and 8 are primarily working on improving their gross motor skills, and they are usually unable to process the finer details of technique, timing, angling, and making connections amongst techniques. By the time a child is 9 or ten, he/she is generally able to pick up on these concepts and other nuances of combatives (base, posture, structure, speed, strength, footwork, etc.).

This of course does not mean that children under eight years of age do not benefit technically. Martial arts drills that incorporate fundamental movement and control of one’s entire body will build core strength in a child, and will aid in the further development of coordination and overall agility - this amplifies the effectiveness of technique as children grow, learn, and develop over time. In addition, a child’s learning can never be rigidly categorized by age - although there are general guidelines to consider when grouping children together by age, not all children will develop at the same pace. This individualized progression for child development occurs with advancement in maturity (responsibility), as well as advancement in physical abilities.

However, deeper technical concepts can be explained to adults more easily, and generally, in less time. Adults tend to conceptualize and articulate their understandings with a greater vocabulary. This higher level of communication speeds up their learning curve and causes them to accelerate through a curriculum faster. A child, on the other hand, is continuing to build his/her vocabulary, and this early-stage development forces them to rely on visual cues, rather than verbal cues. Young children need to learn through active engagement in fundamental movements that are scaffolded toward basic techniques (their verbal vocabulary and understanding of descriptive explanations remains in early development).

Focus and Discipline

Setting aside improved cognition and advanced executive functioning, adults also tend to be more focused, self-disciplined, and more motivated to learn than children. Adults also tend to have more specific goals (short-term and long-term) than children. So, it is important to evaluate adult students and understand their aspirations to tailor your teaching in order to help them see the value and connections between the instruction, and their goals.

One key down-side in teaching martial arts to adults, is that they are often less willing to take risks than kids for many reasons. Adults have a mature development and higher understanding of social ranking and acceptance, so they often fear embarrassing themselves by making mistakes, and don’t want to speak up unless they have the right answer (adults often prefer to stay in their “comfort zone”). Adults are also more educationally developed, so adults often try to out-think their instructors (when they should be listening).

Children, on the other hand, tend to be more receptive to trying new things, and their brains are naturally wired with a desire to learn and grow. Although children can certainly be stubborn (and develop a “know-it-all attitude), they tend to be more exploratory, and willing to listen to an authoritative voice.

Conclusions

The reality of teaching and learning is that all answers lead to further clarification and there are often many answers for the same question. Good teachers guide their practice through an understanding of the conceptions that a student holds, and why the student has such conceptions. A good instructor also knows how to tailor the message to match the audience, so that the pacing is proper for the student’s individual development. It is through one-to-one dialogue and specific assessments that the teacher is able to refine practices for a specific student, in order to help that student move forward on his/ her continuum of learning.